A periodic column published in The Reader, DIS|PLACE is my first foray into opinion writing. DIS|PLACE is an outsider’s perspective intended to encourage debate and challenge social constructs.

White Supremacy Thrives in Fear

I still remember the dread I felt, waking up at 3 a.m. in Johannesburg. The numbers of my alarm clock casting a red glare in the dark, my heart pumping loudly in my chest, my ears strained for the sound of footsteps rustling through the grass outside.

I often woke at that time, jerked out of sleep by an ever-present fear of our home being robbed. When they did break in, they knocked the front door down with an axe. That was four years after my father was gunned down in downtown Johannesburg. And not long before my uncle survived a massacre at a convenience store and a man mugged my mother on the street.

Johannesburg in the 1990s was in a race-to-the-bottom contest for titles like “most dangerous city on earth.” After apartheid (the system of enforced racial segregation in place from 1948-1994) ended, the government struggled to reorganize the police force, which had been a faithful executor of apartheid rule. Calls for help were largely unanswered.

Today, violence has spread to every corner of South Africa, which has the fifth highest crime rate in the world. It is rife and brutal. So, it’s not hard to imagine the relief felt by the 59 white farmers who arrived in the U.S. on May 12 with refugee status, leading their kids and waving small American flags.

But while the fear they are fleeing is legitimate, it is not more so than the fear that every South African feels in a country where crime is out of control.

Donald Trump’s claims that these farmers are victims of a “white genocide” are patently unfounded. This myth has been spread by right-wing groups with their own motivations to stir discord. But those who believe it don’t simply lack the necessary skepticism we all need when browsing social media. They believe it because it echoes a deeply ingrained sentiment that didn’t disappear with Nelson Mandela’s election in South Africa or with Barack Obama’s in America.

It’s a belief as old as both countries and one that lingers like an oft-dormant yet forever-present disease: They deserve more. It’s unacceptable for whites to suffer. It is expected for blacks to suffer.

While attacks on farms have brought global attention and protests, Black people bear the brunt of unchecked crime in South Africa. Between October and December 2024, 6,953 people were murdered in the country. The vast majority lived in townships, which are primarily home to Black and multiracial South Africans. During that same period, there were 68 attacks in rural communities and 12 murders.

If Trump had opened the path to refugee status for all South Africans fleeing crime, I would have applauded it. But, instead, he elevated the suffering of white farmers as uniquely deserving of protection while slamming the door to non-white refugees fleeing war zones and asylum seekers fleeing cartel violence.

Many South Africans denounced Trump’s offer. After living and working together for 30 years, most are proud members of the Mandela-christened Rainbow Nation.

At least they aspire to be. But the notion of white supremacy is insidious. It surfaces when tensions are high, and it requires fearless assessments of our own prejudices to root it out.

When I immigrated to the U.S. at 19, I brought a lifetime of racist views I didn’t know I had. I was taught at school that Black people had smaller brains — that they needed whites to take care of them because they were biologically inferior. Their subservience had been reinforced continually as I interacted with them only as domestic workers and laborers and Black leaders were censored in the media.

But when I began working as a journalist in the U.S., my perceptions were challenged. I interviewed people from all backgrounds and my job necessitated that I understand them well enough to write about them. South Africa established its own form of structured dialogue after apartheid. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission brought assailants face to face with their victims and aired the atrocities of institutionalized racism. It was a model of racial reconciliation.

But harmony cannot exist in a war zone. We are tribal by nature, and when we feel threatened, we are more likely to blame and dehumanize those outside of our group. Mandela’s Rainbow Nation will always fall short of the dream while South Africans live in fear.

I still feel afraid when I think of visiting South Africa. But after 25 years of living in relative safety and challenging my own perceptions, I have learned to separate my fears from fact and can see the lies in the white genocide stories and the racism in Trump’s policies. Trauma and fear may disguise our prejudices, but they are hidden in plain sight if we are brave enough to look for them.

Blame the Enablers, the Aiders and Abetters

What we saw Wednesday at the U.S. Capitol was shocking. Horrifying. It made me embarrassed to be an American. Even if I can qualify that with South African-American. But one thing it wasn’t was surprising. Or at least it shouldn’t have been.

What Can You Do for Democracy?

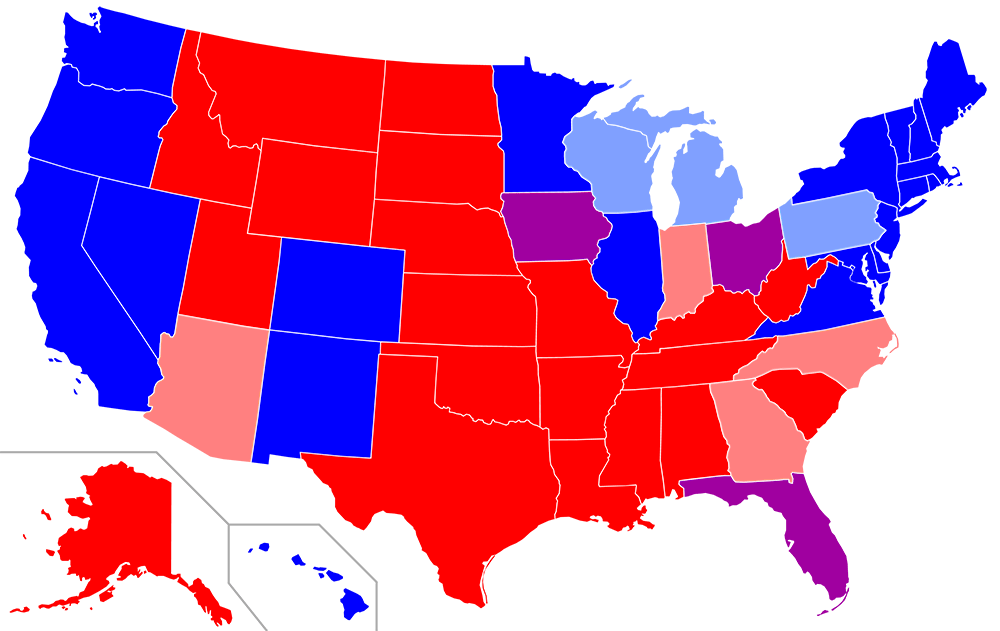

Move to a Red State.

As I write this, President Donald Trump is still doing everything once unthinkable to overturn the election results. Fortunately, he has not succeeded — and he is unlikely to. The independence of the U.S. court and electoral systems have so far proved steadfast.

But the election should never have been this close. And, in fact, it wasn’t.

What to Do in the Face of Tyranny?

As I watched the news this summer, I thought — this makes sense.

Our cities burned, either from raging wildfires or violent clashes in the streets. Federal troops invaded towns, peaceful protesters were gassed, and every day, tens of thousands of Americans got sick and hundreds more died.

It’s a tragic, but entirely fitting, end to our collective journey into the dumpster fire that began four years ago.

What I Learned About Racism Growing Up in Apartheid South Africa

During apartheid in South Africa, racial segregation was a science.

We were divided, not only by color, but by language, tribe and culture. Black tribes were divided and pitted against each other. “Coloureds,” a uniquely South African racial mix, were categorized separately from Blacks and Asians. Whites, the only ones afforded full rights, were less formally separated by language. In essence, it was the Jim Crow South, sustained through the mid-1990s.